Building your first agentic system

The While Loop is the Easy Part: 5 Lessons from building Agentic systems

PS: Content and direction are mine, article heavily edited using AI.

2025 was called the year of agents. But until Claude Code shipped, truly agentic systems were sparse. I had built a multi-agent system earlier (read here), but it was more orchestration than agentic.

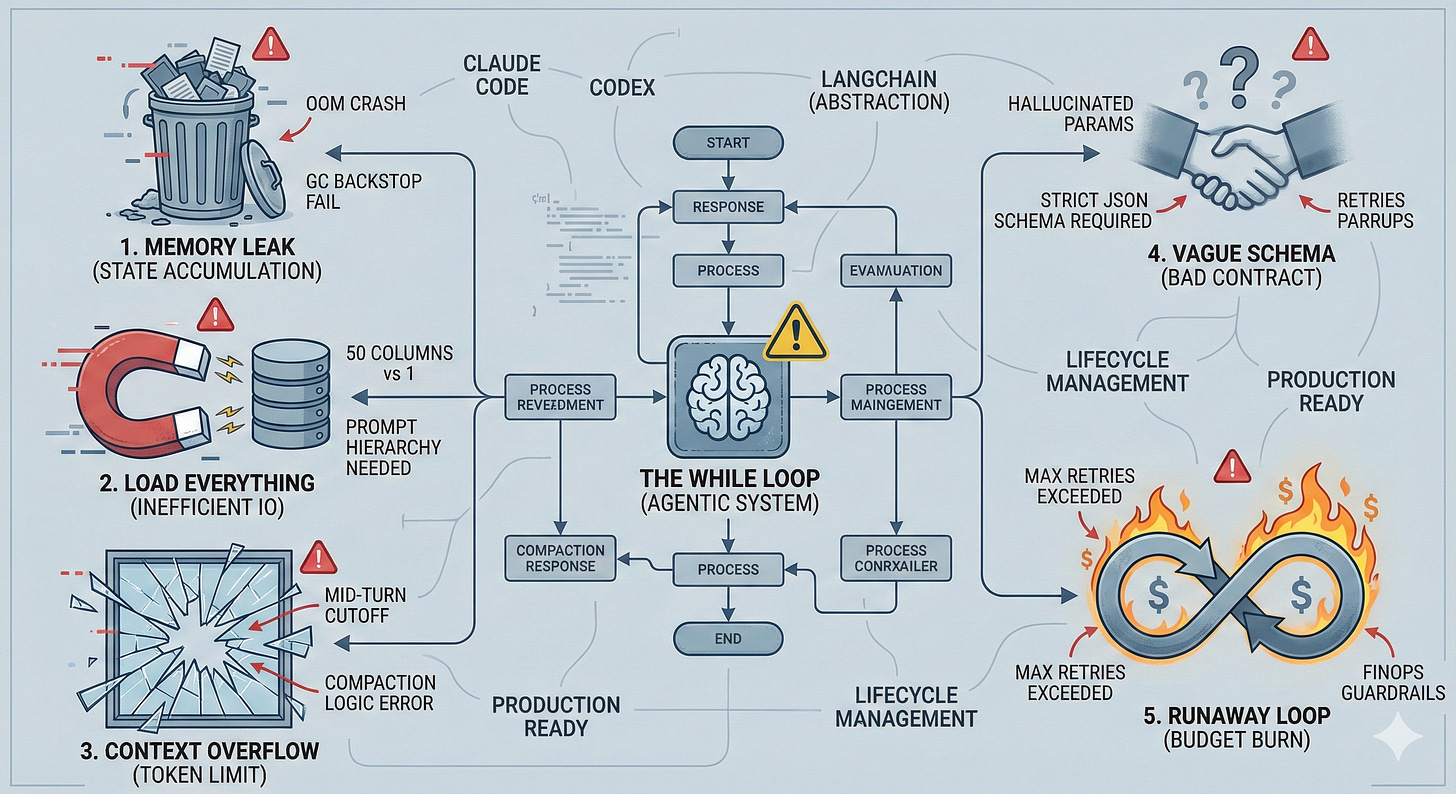

Then it struck me: Claude Code, Codex — they’re just while loops.

After exploring open-source tools and using Claude Code and Codex, I built a data analysis agent: upload a file, ask any question, and the agent figures out the columns it needs, runs the analysis, and returns a summary with charts. Code shared here.

It worked great in development. Then it broke. I’ve built 4-5 versions next, all of which failed at various stages before reaching an optimal stage.

This post covers five reliability lessons that don’t show up in tutorials — but will show up in your debugging logs.

TL;DR: The Agent Builder Checklist

Memory isn’t free: Runtimes (GC or Ownership) won't save you from logical leaks in session state. Track your memory usage and explicitly clear intermediate resources after every turn.

Prompt for efficiency: LLMs are greedy; they will load 50 columns when they need 1. Use proper context engineering.

Compact between turns: Never truncate context mid-reasoning. Track token usage and prune “dead weight” before the next turn starts.

Schemas are contracts: Vague tool descriptions lead to hallucinated parameters. Use strict, explicit schemas.

Set circuit breakers: Agents loop until they fail or go broke. Implement hard limits on tool calls and retries.

1) Memory That Never Dies

The assumption: Each agent turn is stateless. Resources clean up automatically.

The reality: Most implementations keep session state between tool calls — intermediate results, loaded resources, computed values. That state accumulates.

def execute_tool(self, tool_name, args):

result = run_tool(tool_name, args)

self.resources[args["name"]] = result # accumulates forever

return resultMultiply that by 100 concurrent users running multi-step chains. Memory climbs. Garbage collection can’t help because references still exist. Eventually: OOM crashes.

What happened: Data files loaded for analysis stayed in RAM after each turn. Python’s GC couldn’t reclaim them because the session held references. With concurrent users, memory grew unbounded until containers crashed.

The fix: Explicit lifecycle management (clear references + close handles + enforce TTL/LRU).

import gc

def reset_after_turn(session):

# If your objects have a close()/cleanup() method, call it here.

for key, obj in list(session.resources.items()):

try:

if hasattr(obj, "close"):

obj.close()

finally:

session.resources.pop(key, None)

del obj # break references (especially helpful for complex graphs)

session.resources.clear()

gc.collect() # GC is a backstop; real fix is removing session refs + closing handles

Key insight: GC is a backstop, not a solution. If your session holds references, memory won't be freed. This is especially dangerous when using data libraries like Pandas or NumPy—they often allocate memory in C-extensions that Python’s GC struggles to track.Explicitly drop references + close resources, and enforce TTL/LRU for bounded session state.

2) The Agent Loads Everything

The assumption: The model will make efficient choices about resource loading.

The reality: LLMs optimize for correctness, not efficiency. Given “load everything” vs “load only what’s needed,” they choose safety every time.

What happened: I provided three loading tools — sample (schema only), partial (specific columns), and full (everything). The agent consistently chose full loads even for “what’s the average of column X?” Loading 50 columns when it needed 1.

The fix: It wasn’t better tools — it was a better system prompt. Don’t just provide tools; tell the agent when to use each:

LOADING STRATEGY (follow this order):

1) get_metadata() - Check what's available FIRST

2) load_partial(fields) - PRIMARY: Load ONLY what's needed

3) load_full() - RARE: Only when ALL fields are required

Examples:

- "average sales by region" -> load_partial(["region", "sales"])

- "filter by date" -> load_partial(["date", "amount"])

The pattern: provide a clear hierarchy with concrete examples. It’s still prompt engineering in 2026.

3) Context Overflow Mid-Turn

The assumption: Context windows are large enough.

The reality: In practice, I found ~100k–250k tokens to be the usable range. The industry is moving away from large context windows, we now talk doing context engineering. So when agent loops accumulate context fast: tool calls, tool results, intermediate reasoning — it adds up, we need to compact the context. Hit the limit mid-turn and the user gets nothing.

A typical turn:

user message (100 tokens)

system prompt (1000)

tool call (300)

tool result (2000)

another call (100)

another result (1500)

After a few turns, you’re at 80% capacity. One unexpectedly large tool result (e.g., analysis output on a 1000×10 table) and you hit the wall mid-turn. The model can’t complete. The user’s question goes unanswered.

What happened: Our compaction logic triggered mid-turn when tokens exceeded a threshold. This interrupted the agent’s reasoning. Users asked questions and got nothing back.

The fix: Compact between turns, never during. Also be deliberate about what you compact: messages, tool outputs, raw data dumps — anything that won’t help the next turn. The goal here is Context Precision. By compacting between turns, you ensure the agent starts every new reasoning step with a "clean" but relevant history, rather than hitting a wall halfway through a critical computation.

def run_agent_turn(session, message):

# Check BEFORE the turn, not during

if session.total_tokens > (MAX_TOKENS * 0.80):

compact_history(session) # summarize / prune / store large artifacts out-of-band

return execute_turn(session, message)

Don’t punish the user for token limits. Track usage and proactively compact before hitting the ceiling (unless your KPI is token usage, not outcomes, Claude Code - I am talking to you).

4) Tool Schemas Are Your API Contract

The assumption: Tool descriptions are just documentation for the model.

The reality: Tool schemas are the contract between the model and your tool runner. The model uses them to decide what to call and how. Your runner uses them to validate and execute. Vague schemas = wrong calls = runtime errors on both sides.

{

"name": "process_data",

"description": "Process the data",

"parameters": {

"data": { "type": "string" },

"options": { "type": "object" }

}

}

What data? What format? What options? The model guesses — and guesses wrong.

The fix: Whether you’re using JSON Schema or a simplified tool schema format or a pydantic type-safe models, the point is: make it strict.Strict, explicit schemas:

{

"name": "load_dataset_columns",

"description": "Load specific columns from a dataset. Returns a DataFrame.",

"parameters": {

"dataset_name": {

"type": "string",

"description": "Name from get_dataset_info()"

},

"columns": {

"type": "array",

"items": { "type": "string" },

"description": "Column names to load"

},

"df_name": {

"type": "string",

"description": "Variable name for the DataFrame in REPL"

}

},

"required": ["dataset_name", "columns", "df_name"]

}

Key Insights:

prefer explicit enums over free-form strings

describe relationships between tools (“use output from X”)

document return values (shape + keys)

mark required fields clearly

The model can only be as precise as your schema allows.

5) Runaway Loops Will Burn Your Budget

The assumption: The agent will finish in a reasonable number of steps.

The reality: Without limits, agents can loop indefinitely. A confused model retries the same failing tool. A complex query spawns endless sub-tasks. Each iteration costs tokens, time, and money.

What happened: An edge case caused the agent to repeatedly call the same tool with slightly different parameters, expecting different results.

The fix: Hard limits at multiple levels: max tool calls per turn, max retries per tool, and a timeout per turn.

MAX_TOOL_CALLS_PER_TURN = 10

MAX_RETRIES_SAME_TOOL = 3

def run_agent_turn(session, message):

tool_calls = 0

tool_counts = {}

while not done:

response = model.generate(...)

if response.has_tool_calls:

for call in response.tool_calls:

tool_counts[call.name] = tool_counts.get(call.name, 0) + 1

if tool_counts[call.name] > MAX_RETRIES_SAME_TOOL:

return {"error": "Tool retry limit exceeded"}

tool_calls += len(response.tool_calls)

if tool_calls > MAX_TOOL_CALLS_PER_TURN:

return {"error": "Tool call limit exceeded"}

When limits hit, fail gracefully with a clear message. The user can retry with a narrower question, or you can ask a clarifying question. Also add per-tool timeouts, exponential backoff, and a circuit breaker when the same error repeats.

Why Not Use Agentic Libraries?

You might ask: why build from primitives instead of using LangChain, CrewAI, or similar frameworks?

Honestly, I chose not to. These libraries are still maturing, and the tools I admired — Claude Code, Codex — were built on raw foundations, not abstractions. I wanted to understand the while loop, not hide it.

That said, frameworks have their place. If you need to ship fast and your use case fits their patterns, use them. But if you’re debugging a memory leak at 2:30 AM (yes, I hit the Claude limits too 😅), you’ll want to know what’s actually happening under the hood.

Conclusion

The biggest mistake is thinking an agent is just “an LLM in a while loop with tools.” It’s not. It’s a system with:

State management (sessions, resources, context)

Resource constraints (memory, tokens, time)

Failure modes (partial, silent, cascading)

Concurrency concerns (multiple users, multiple turns)

The while loop is the easy part. Everything around it — context management, resource efficiency, error handling, prompt engineering — that’s where the work lives.

Build agents like you’d build any production system: explicit resource management, defensive error handling, clear contracts, and guardrails everywhere.

If you’re interested in the intersection of LLM orchestration and reliable AI engineering to solve analytics and other interesting problems, subscribe.